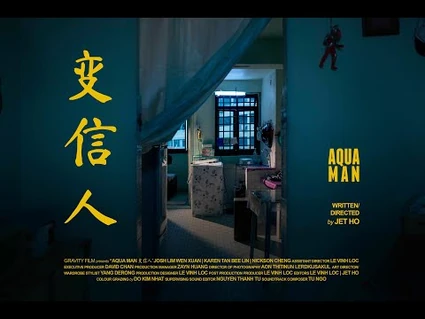

Aqua Man (变信人) is a short film on conversion therapy written and directed by Jet Ho. It premiered on YouTube on 19 December 2020[1].

Description:

"Set in the 2000s, Aqua Man talks about the emotional transformation of a young boy, Junjie, and its religious dilemma of being a gay Christian individual in Singapore.

Aqua ah kua, ah kwa /kuah, kʊɑː/ n. & a. [poss. Hk. (邪 k’hwa (sëà distorted, perverse (Medhurst); Mand. kuā (literary language) askew, crooked, aslant, oblique (+ xié evil, heretical, irregular) (Comp. Chi.–Eng. Dict.)] Also ah gua, ah qua, and abbrev. to AK, AQ. derog. A n. 1 An effeminate man. 2 A male transvestite. B a. Effeminate, sissy."

It was Ho's directorial debut, which although taking only one month to conceptualise, write, cast and produce, was immensely difficult for him to promote. The reason was Singapore's draconian censorship laws regarding homosexuality. The story of student Jun Jie, his distressed mom, and Bible-armed pastor was rejected at least 15 times by streaming platforms and film festivals[2].

"Aqua" is phonetically similar to the derogatory Hokkien term for gay men, "Ah Kua", which literally means transvestite. In Ho’s film, actor Josh Lim is the titular character who comes home one day to find his mother has brought a pastor to pray the gay out of him with a praying ritual form of conversion therapy. Because of the subject matter, Aqua Man could not be shown on television, as films featuring characters who were gay, regarded as an “alternative lifestyle” by government censors, were automatically rated R21.

The restriction, most often applied to movies containing nudity, was not something Ho was happy with. After all, he wanted to reach those who would most identify with his protagonist. He said that it was a societal problem that started out even with children at a very young age, referring to the younger generation who struggled with their sexual identity. He stressed that it had nothing to do with explicit pornographic material that perhaps needed a higher age rating. Therefore, he had no choice but to premiere his film on YouTube where it struggled to find a large audience.

Ho, a commercial photographer for the National Museum and National Geographic Channel explained he was motivated to make his movie by the lack of a quality queer representation in Singaporean television shows and movies. Queer characters portrayed as regular people were unheard of on national television where they were relegated to cross-dressing tropes by the likes of Jack Neo and drag queen Kumar, or are sources of comic relief, such as transgender comedian Abigail Chay.

Ho lamented that mainstream television just included queer characters to portray them in a very bad light or having a pernicious influence, thereby propagating a misrepresentation of the LGBT population in Singapore. He elaborated that if Disney had one gay character in a movie and it was premiering in Singapore, a lot of people would make a big fuss out of it. Indeed Disney’s "Beauty and the Beast" did kick up some dust in 2017 from church councils, which denounced the film winning a PG-rating despite the inclusion of a gay character. That said, Ho felt that Singaporeans were more open to discussing gender identity today than two decades prior, pointing out that Aqua Man was set nearly 20 years ago, a time he thought Singapore’s cultural conservatism was at its peak.

In 2021, arch-conservatives appeared to feel they were on the defensive, denouncing “woke cancel mobs” over arguments that seemed to have moved on from their point of view as negative LGBT views continued to tick down. Singapore’s strain of evangelical Christianity remained a potent force and the intersection between faith and family was an area Ho mined for his film. Ho noted that when the parents of an LGBT child faced such a problem in Singapore's very conservative society, they often sought a solution in the church or with religious institutions but the answer to whether it was the right or the most moral approach was nobody's to judge. He found this dilemma in the film very interesting because there was no right or wrong answer.

Ho, who was not Christian, had only heard stories of conversion therapy. So, before filming, he delved a little deeper into the topic by attending weekly sermons at churches and interviewing pastors in the hope of portraying them more accurately and was grateful for the opportunity. He did not want to cast any church or any organization in a bad light but he aimed to make the whole film look as authentic as possible. After interacting with the church, he was very thankful to emerge with the concept that they were “loving” and “very understanding.”

Even though Ho forked out SGD$16,000 (USD$12,000) to make the film, even film festivals and competitions turned him down. The main problem was that when he tried to send it out to a few film competitions, he was not notified about whether he had lost or received any feedback at all. Locally, on streaming platforms, he sent out a few emails to the organisations' main email addresses and even directly to people who worked in them but be received zero replies. That was how dire it was as they were so repulsed by LGBT-centric films.

Ho also submitted his film to the Singapore International Film Festival and HBO Asia’s Invisible Stories series, marketing it as unearthing Singapore's untold stories. They were among the more than a dozen platforms that rejected him or ignored his inquiries but he took comfort in one HBO representative’s note. Even though his team clinch any avenues, it was actually a great relief because the female representative personally wrote an email to them, and that was the only reply they got. Initially, he really thought the film was so abysmal and negative to the extent that it did not deserve a place or anything at all for that matter. Although uploading the film directly to YouTube was not his first choice, Ho was gratified by the response he garnered.

After the film was produced, it was very astonishing to find that many people actually reached out to say that they personally experienced the same thing so it became a true story that he wrote. Initially, he just dictated the narrative and thought it would be something interesting to depict but it became a genuine account, corroborated by people who watched the movie. It was also shared by LGBT-friendly counselling organisation Oogachaga on its Facebook page.

Ho was determined that it would not be the end of the road and strived to promote Aqua Man to a wider audience. He also started writing another script and pledged to continue persueing stories on social issues such as transgender issues, racism, and abuse.

He opined that Singapore had to have its own culture when it came to filmmaking because the country's culture her people's identity. As such, they should portray more and show more. Instead of sweeping these topics under the carpet, Singaporeans should embrace them and move forward. Trying to conceal all LGBT-centric material was not going to be helpful for them to progress into a more empathetic society.

See also[]

References[]

- Carolyn Teo, "Gay ‘conversion’ is being debated in Singapore. So it’s too bad few will see ‘Aqua Man.’", Yahoo! Style, 22 March 2021[3].