Emeritus Professor S Shan Ratnam (full name Sittampalam s/o Shanmugaratnam) (4 July 1928, Ceylon to 6 August 2001, Singapore) was the professor and head of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology at Singapore's National University Hospital specialising in human reproduction research. Sex reassignment surgery for transgender people was his research interest for three decades and his forte. He performed Singapore's first sex change operation in 1971.

At the peak of his career, he represented Singapore as the secretary general of the Asia and Oceania Federation of Obstetrics and Gynaecology (AOFOG) and was a member of the executive board, president-elect and president of the International Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics (FIGO). Through these two organisations, he helped place Singapore on the international medical arena and established himself as a prominent figure in the O&G world.

His work on contraception contributed to Singapore's success in population control. The National University Hospital research laboratory for prostaglandin research was initiated and propelled by his vision and energy. He was also the founder of the in vitro fertilisation (IVF) programme which has given hope to many childless couples. Sittampalam Shanmugaratnam shortened his own name to Shan Ratnam, and he is credited as S Shan Ratnam or SS Ratnam in all official media.

Early life[]

In an interview in 1995, Ratnam said that his father had settled in Malaya for three generations while his mother came from Ceylon.

Ratnam claimed that it was an old practice among local-born Indian men to marry brides born from their native country. However, such brides usually returned to their native country for confinement after marriage.

Ratnam was born in Chullipuram, Jaffna District, Sri Lanka in 1928 to parents of Sri Lankan Tamil descent. He returned to Kuala Lumpur at the age of six months and spent most of his early life there. In the meantime, his father worked in the courts, and became the Official Assignee of the Supreme Court in Kuala Lumpur just before the Japanese Occupation in 1942. During his early years, Ratnam was greatly influenced by his mother, who taught Ratnam the Tamil language as well as the Ramayana (Hindu epic). At the age of six, his mother had told him to help others instead of praying at the temple, saying:

"You don't need to pray. You don't need to go to temple. But every day, try to help someone. That is the better form of prayer than going to temple. And try never to say no to anybody. Because when you say no, you hurt somebody. Even if it is something that you have to give, just give. In giving you help people."

Ratnam's mother's ideologies greatly influenced his later life. In the interview, Ratnam confessed that he never tried to say "no", and in the case of saying "no", he would always find time to analyze to see what he had done was the right thing and whether he could have avoided saying "no".

Ratnam's father was nearly killed by the Japanese and was instructed to be beheaded within one to two days time due to his impulsive nature not to obey the Japanese troops. A Japanese woman who was married to an Indian man managed to save his father just before he was beheaded.

Ratnam's mother was diagnosed with rectal cancer at the age of 36 during the Japanese Occupation. Considering that their bond was “inseparable”, Ratnam nursed and attended to his mother in light of a lack of alternatives. There was no official healthcare nor access to painkillers available during the occupation. As a teenager, he would often cycle in the middle of the night through graveyards and forests to get crude opium or marijuana for his suffering mother. She died at the age of 38 after suffering for at least three and a half years. To add to the family’s troubles, Ratnam’s younger brother, who was about four, also passed away due to tuberculous meningitis. Ratnam had three other siblings, including an older sister. These events influenced Ratnam to change his ambition from becoming an engineer to taking up medicine as career – he saw the positive and rehabilitative impact that doctors could have on lives.

Achievements[]

As a young man, Ratnam began his career as a houseman (trainee medical officer) at the Singapore General Hospital in 1959. He also began teaching at the University of Singapore in 1963.

After obtaining his M.R.C.O.G (and later, the F.R.C.S.) in 1964 in England, he was coveted to the post of Professor and Head of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology in Singapore, a post which he held for 25 years.

In 1972, Ratnam's Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology at Kandang Kerbau Hospital received the accolade as being one of 13 research centres in human reproduction in the world, recognition conferred by the World Health Organization.

In 1970 he was made Chief Examiner and Director (1972) of Postgraduate Medical Studies at NUS. Member of the editorial boards of several learned journals including the International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology and the International Journal of Prenatal and Perinatal Studies.

Ratnam contributed greatly to reproductive biology and won worldwide acclaim for his work. A book, 'Cries from Within', was written to explain the procedure for sex change operations in 1970. He also added greatly to his corpus of medical advances by giving Asia its first test tube baby through the in-vitro fertilisation process in 1983. Ratnam experimented with IVF on rats prior to his first successful attempt on using the technique to conceive human babies.

Prof Ratnam greeting President Benjamin Sheares when he arrives at the Hilton Singapore to open the 4-day Asian Federation of Obstetrics and Gynaecology First Inter-Congress on 27 April 1976. (Photo source: National Archives of Singapore[1]).

In 1977, he was awarded the Singapore Public Administration Gold Medal. His learned articles and conference papers ran into the hundreds, and he has 15 edited or co-edited books to his credit (Cf. Library of Congress Online Catalog, under Name Browse: Ratnam, S.S.)

Ratnam served as the secretary general of the Asia and Oceania Federation of Obstetrics and Gynaecology for seventeen years, as member of the executive board of the International Federation of Obstetrics and Gynaecology from 1969 to 1982, president-elect from 1982 to 1985, and president from 1985 to 1988. Ratnam was also Visiting Professor to the UK in 1982 and South Africa in 1994.

In 1987, he pioneered the procedure of giving birth to a baby born from a frozen embryo. The world's first micro injection baby via human ampullary coculture was also developed by him in 1991.

Ratnam greatly contributed to gynaecology in terms of his paper works. He had credit to 378 research papers in the referred International Journals, 232 research papers in the referred local and regional journals, including nineteen non-referred journals.

His career as a research scientist and teacher continued unabated at the National University of Singapore despite his official retirement in 1998, as Emeritus Professor of Gynaecology and Obstetrics. He was a noted world authority in sex change operations[3], breaking new ground in sex reassignment surgery, embryo replacement, in vitro fertilisation and the in vitro control of fertilisation.

Singapore's first sex reassignment operation[]

Ratnam successfully performed the first sex change surgery in Singapore on Friday, 30 July 1971 at Kandang Kerbau Hospital[4]. The operation involved a 24-year-old assigned male at birth individual and was the first procedure of its kind carried out in Singapore as well as in Asia. There had been previous “sex-change” operations performed locally, but these mostly involved patients who had both male and female genitalia (hermaphrodites) and the removal of one set of genitalia. The 1971 operation was regarded as a first because it involved a surgical conversion aimed at functionally changing a person's sex.

The patient was a 24-year-old ethnic Chinese Singapore citizen. Her name was initially kept secret, but her background was later made public in a book, which also revealed her name as "Shonna". The eldest son in a family of five with two younger sisters, she lived in constant fear as a child because her father was a hot-tempered and aggressive dentist who was often physically violent with his wife. This caused her much psychological trauma as she witnessed her mother suffer multiple beatings at the hands of her father. Stitches and trips to the hospital became commonplace in a household that was supposed to be a bastion of safety and security. Eventually, Shonna moved to her grandmother's abode although she still maintained frequent contact with her mother and two younger sisters. Her grandmother raised her, dressing her up as a female and it was through the elderly woman that Shonna was given up for adoption by the goddess Guanyin (Goddess of Mercy in Buddhism) at their nearby temple. In her teenage years, she associated with other cross-dressers before frequenting the transvestite and transsexual scene at Bugis Street as an adult.

Shonna’s teenage years were no better than her childhood. At school, she was performing abysmally and was unsuccessful in her attempts at obtaining a secondary-level certificate. It did not help that she was often bullied for her appearance. Male students would take her to the movies and force her to masturbate them. Her father tried to get her to work as an assistant at his dental clinic for a while, though this was short-lived. After embarrassing remarks about Shonna’s ambiguous gender, the dentist banished her to perform chores at home. A year before her father died in 1966, Shonna started looking for work on her own. From the age of 16, she first worked as a sales assistant, then as a housemaid for a European man whom she had an affair with and who subsequently forced her to leave the job. She then found work in a bank. Her next occupation was a public relations officer in a hotel. During this stint, Shonna entered a Miss Beauty contest and won the second prize. As a result, she was allowed to model part-time for advertisements and was soon featured in Her World magazine. It was also during this period that Shonna joined a cabaret where she was known as "Mama Chan" and started a social escort service.

While her professional life had started to take off, her personal life was still in a shambles. The woman wanted to be a serious model, get married to a man and settle down. These were things that her physical body and the prevailing laws of the era would not allow her to do. Desperation drove her to attempt suicide twice and left her on the verge of another attempt to kill herself. This was when she decided to seek Professor S Shan Ratnam’s help. Having lived as a woman for some time, she first consulted Ratnam, then senior lecturer in the University of Singapore’s Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, in 1969. She was suffering sexual and emotional problems, which had led to two suicide attempts.

In later years, Ratnam recounted his experience of seeing the young woman sitting outside his office: “She was so attractive, I couldn’t take my eyes off her.” Deep down, he knew that something was wrong – the women who would come see him this late and alone usually wanted an abortion or help with an awkward situation. Nonetheless, he invited the woman into his office and sat her down. “Professor, I want a sex change operation,” she said very frankly. Surprised, he leaned back on his chair and responded, “Why come to me? I don’t know anything about transsexualism”. At that point, sex change operations were virtually unheard of around the world, and there was little medical literature surrounding the topic.

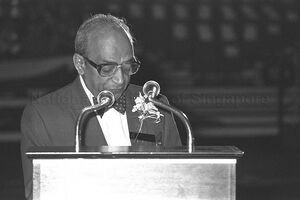

Prof Ratnam giving a speech at the opening ceremony of the 13th World Congress of Gynaecology and Obstetrics at the Singapore Indoor Stadium on 15 September 1991. (Photo source: National Archives of Singapore[2]).

“Professor, you have the right to say no, I’ll accept it. But you may not see me alive again,” she said as she pulled down her shirt to show a large cut mark across her neck. Not knowing what to do, the professor referred her to the psychiatric clinic, hoping that she would not come back. Ratnam explained to her that he had no experience in sex change surgery, but she persisted and continued to visit his clinic weekly. Every evening, at around six, she would wait outside Ratnam’s office, asking him if there were any updates on her case. Eventually, the psychiatrist, Dr Tsoi Wing Foo, wrote back to Ratnam, telling him that Shonna was not only able to give informed consent for the operation, but would also greatly benefit from it. She had been diagnosed with gender dysphoria, which meant that she possessed a continuous sense of inappropriateness about her anatomic sex and a desire to discard her genitalia and live as a member of the opposite sex. A total of six to nine months of medical and psychiatric tests had to be carried out before the Shonna could undergo the operation. After the results were reported, Ratnam had no choice but to give in. He began to research the subject of transsexualism and sex reassignment surgery. In preparing for what was to eventually be Asia’s first sex change operation, Ratnam referred to a technique created by Singapore’s President (and former professor of gynaecology) Benjamin Sheares. Called the Sheares vaginoplasty, the groundbreaking technique was originally used to create an artificial vagina for those born without one. Ratnam adopted and modified this technique for in sex change operations. He then familiarised himself with the surgery by practising on cadavers.

Shonna underwent a psychological analysis by a team of psychiatrists who confirmed that she was a transgender woman who required surgery. A diagnosis of transsexualism required that the patient possess a continuous sense of inappropriateness about his or her anatomic sex, a desire to discard his or her genitalia and live as a member of the opposite sex, and the absence of physical intersex symptoms or genetic abnormalities. Furthermore, his or her gender confusion (gender dysphoria) must not be caused by other disorders such as schizophrenia. The patient was also cautioned that the surgery would be irreversible, potentially involved a number of complications and required a prolonged follow-up period.

As Shonna’s operation loomed, Ratnam reached out to the Ministry of Health to seek legal clearance. The ministry granted it as long as the procedure was done in secret and without publicity. Nurses, doctors and other workers at the hospital were informed about the instructions. After consideration of the Shonna’s psychological profile and the medical expertise involved and with the approval of the ministry, it was decided to proceed with the operation.

On 30 July 1971, the operation was performed by Ratnam and two other top surgeons from the University of Singapore’s Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Associate Professor Khew Khoon Shin and plastic surgeon Mr R Sundarason. Photography of the operation was not permitted and everything was kept secret. That was until a medical student in the operating theatre telephoned his sister, who was then a reporter, to tell her that history was being made. The secret was so badly kept that by the time Prof Ratnam returned to his office after the operation, his phone was constantly ringing. He described the 3-hour operation as a success, with an uneventful post-surgery recovery.

For the first two to three years after Shonna’s operation, Ratnam conceded that he was very worried. Considering that sex change operations were relatively new, he was fearful that patients would regret and resent the irreversible procedure after a few years. Even his own colleagues were talking behind his back about the surgeries. However, as soon as he started getting letters from patients (some calling him a “saviour”) thanking him for his help, he knew he was doing the right thing. According to him, even recovered cancer patients were not as joyous as these individuals. This conviction led Ratnam to later establish the Gender Identity Clinic specialising in sex reassignment surgery at the National University Hospital.

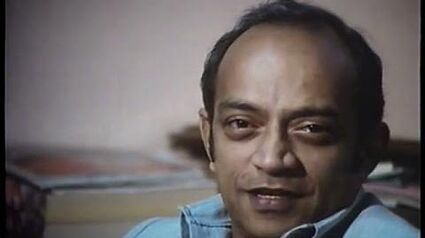

His work with transsexual patients was showcased in a documentary entitled "Shocking Asia" in 1974. In it, Ratnam was interviewed about his background with male-to-female transgender patients. He talked about how he first got involved with "the problem" (referring to the patient's penis) and how he used cadavers to come up with his technique of sex reassignment surgery. It also showed his assistant, Dr Lim, taking some final photographs of a patient before her surgery. However, Ratnam is believed to have been unhappy with the final tenor and packaging of the documentary, which can be regarded as a mondo film, as he was probably led by the producers to believe that it would be a scientific, non-sensationalistic project.

Prof. Shan Ratnam & sex change ops in S'pore (1974)

Ratnam later trained other gynaecologists like Assoc Prof Arunachalam Ilancheran who joined him in 1979 and his nephew Dr C Anandakumar to perform the procedure.

Lobbying to allow post-op transgenders to change particulars on ICs and passports[]

- Main article: Archive of "'Help sex-change patients to a normal life' plea", The Straits Times, 25 November 1973

On 25 November 1973, Prof. Ratnam made a speech during the International Y's Men's Club lunch meeting at Hotel Equatorial imploring the Government to allow post-operative transgender Singaporeans to change the particulars on their personal documents so that they could have a better chance of leading normal lives.

A policy directive was subsequently instituted at the National Registration Department to enable them to change the legal gender stated on their national registration identity cards (NRIC) (but not their birth certificates) and other documents which flowed from that, such as their passports. He also advocated that post-operative transsexuals be given the legal right to marry an opposite-sex spouse. This was done without much fanfare via an announcement in parliament by PAP MP and Speaker of Parliament Abdullah Tarmugi that the Women's Charter would be amended to allow this.

Of course, one would not expect just one speech by Prof. Ratnam to accomplish this coup which saw Singapore take the lead worldwide with respect to transgender rights. The LGBT community and general public did not know how this was achieved until Ratnam's protege, Assoc. Prof. Arunachalam Ilancheran revealed during a television discussion forum on thirunangai (Tamil male-to-female transwomen) in 2012 that Ratnam lobbied the Government quietly behind the scenes (see video: [5]).

Later years[]

Ratnam's driving licence was suspended after an episode of driving a vehicle under the influence of alcohol. He suffered a stroke in December 1999.

He died at the age of 73 at 6:55pm on 6 August 2001 at the National University Hospital due to pneumonia.

Timeline[]

Academic credentials[]

- 1957: MBBS Hons, Ceylon

- 1964: Certificate in Exofoliative Cytology, London Postgraduate School of O&G, 1964

- 1964: MRCOG

- 1964: FRCSE (O&G)

- 1977: IRACS

- 1970: University of Singapore (MD)

- 1982: Sims Black Travelling Professorship, RCOG, UK

- 13 Honorary memberships, fellowships and degrees

Career[]

- 1957-61, Singapore General Hospital, Trainee Medical Officer

- 1961-62: Kandang Kerbau Hospital

- 1963-68: Department of O&G, University of Singapore, Lecturer

- 1968-69: Senior Lecturer

- 1970-95: Professor and Head

- 1969: Chairman, ctee for O&G, Graduate School of Medical Studies, National University of Singapore

- 1970: Chief Examiner, M Med in O&G, National University of Singapore

- Member, National Planning and Population Board

- Singapore Planning Asoociation

- 1971-2001: Member

- 1972-82: President

- 1983-84: Council Member

- 1985: Emeritus

- Singapore Planning Asoociation

- 1958: Member, Singapore Medical Association

- 1964-2001: Member

- 1969-72: President

- 1977-78: President

- 1979-93: Council Member

- 1988: Director, Graduate School of Medical Studies, National University of Singapore

- 1969-71: Chairman, Chapter of O&G, Academy of Medicine, Singapore

- 1957-2001: Member

- 1968-2001: Member, Royal Society of Medicine, UK

- 1968-2001: Member, British Medical Association

Honours and awards[]

- Doctor of Science (Honoris Causa), University of Colombo .

- Honorary Fellowships of Obstetrics and Gynaecology societies in Japan, Australia, UK, Sri Lanka, Philippines, Israel, Korea, U.S.A., and at the West African College of Surgeons.

Legacy[]

Many of his former students are now members in the O&G field including the current head of department at the National University Hospital, Dr P C Wong. He was a staunch Hindu during his lifetime. He had two children; one son and one daughter. An O&G centre at Camden Medical Centre was set up in October 2001 and named after him - SSR International Private International. The centre is currently run by his nephew, Dr C Anandakumar.

See also[]

- Arunachalam Ilancheran

- C Anandakumar

- Tsoi Wing Foo

- Kok Lee Peng

- Transgender people in Singapore

- Singapore transgender history

- Sex reassignment surgery in Singapore

References and external links[]

- Who's Who in Singapore, by Who's Who Publications, Low Ker Thiang

- (Cf. Library of Congress Online Catalog, under Name Browse: Ratnam, S.S.)

- Link on past seminar by SSR international

- Dr Nalin Rodrigo, "Professor Shan Ratnam – a fantastic record of work", Ancestry.com, Rootsweb[6].

- Sara Pek, "S. Shan Ratnam", Singapore Infopedia, National Library Board, 2008[7].

- Book prize named after Prof Ratnam. (12 November 2001). The Straits Times. (Microfilm No.: NL23280)

- Chew, M. (1996). Leaders of Singapore. Singapore: Resource Press. (p. 284-288) (Call No.: RSING q920.05957 CHE)

- Nadarajah, I. (3 November 1996). Forum marks another breakthrough for Ratnam. The Straits Times. (Microfilm No.: NL20141)

- Low, K.T. (2000). Who's who in Singapore. Singapore: Who's Who Publishing. (Call No: RSING 920.05957 WHO)

- Khalik, S. (8 August 2001). Man of vision, mentor to many. The Straits Times. (Microfilm No: NL22191)

- Tan K. H. & Tay E. H. (eds.) (2003). The history of obstetrics and gynaecology in Singapore (p. 498-502). Singapore: Obstetrical & Gynaecological Society of Singapore, National Heritage Board. (Call No.: RSING 618.095957 HIS)

- (Jul 1996). Passion that blazes from within. The Alumnus. Issue No. 26. (p.34-36). (Call No.: RSING 378.5957 A)

- Arulkumaran, S., Salmon, Y. & Daniel, R. O. (1994). A short history of the Obstetrical & Gynaecological Society of Singapore 1972-1993. Singapore: The Society. (Call No.: RSING 618.0605957 SHO)

- Ratnam, S. S., Arulkumran, S. & Sen, D. K. (eds.) (1997). Problem oriented approach to obstetrics & gynaecology. Singapore : Oxford University Press. (Call No.: .RSING 618 PRO)

- Ratnam, S. S., Goh, V. H. H. & Tsoi, W. F. (1991). Cries from within: Transsexualism, gender confusion & sex change. Singapore: Longman Singapore. (Call No.: RSING 616.8583 RAT)

- Ratnam, S. S. (ed.) (1979). Adolescent sexuality. Singapore: Singapore University Press for Family Planning Association of Singapore. (Call No.: RSING 301.4175095957 ADO)

- Jeffrey Hays, "Homosexuality, gay life, and sex change surgery in Singapore", Facts and Details, 2008, updated June 015[8].

- "Meet the Doctor Who Successfully Lobbied Singapore’s Government for Trans Rights", The Kopi, 7 February 2021[9].

Acknowledgements[]

This article was written by Roy Tan.